Of Old Radios And Related Items--Published Monthly

More on Motorola and the 53LC3C

BY OLIN SHULER

Web Edition

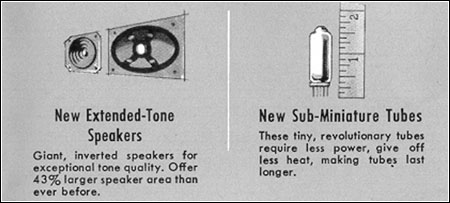

One A.R.C. article frequently spawns another. From his personal experience, Olin Shuler responds here to Jerry Wieland's article on the Motorola 53LC3 in the February 2004 issue of A.R.C. Olin comments on Motorola's use of subminiature tubes and inverted-basket speakers. He also provided a 1953 brochure touting the company's wide ranging electronic products, such as 2-way radios, radar equipment and color TV. Some of the brochure's illustrations are included here. (Editor)

What a pleasant surprise to see a "familiar face" looking back at me in Figure 1 on page 12 of the February 2004 issue of ARC -- specifically, the 1953 Motorola 53LC3 portable clock radio. This radio was built in a Motorola Consumer Products Division plant in Quincy, Illinois. This division was located in an aging, 3-story factory building, still standing today overlooking the Mississippi River at Third & Broadway.

Motorola relocated part of its radio production to Quincy in 1948, expanded in 1950, and by 1956 occupied a new facility at 1400 North 30th Street. It grew to become the world's largest plant devoted solely to the manufacture of radios. Television and audio products followed later.

I worked for Motorola, first as a production tester and inspector, starting in 1950. In late 1951, I left for the Army, returning in late 1953. I rejoined Motorola as a statistical clerk in the Production Engineering Department. The 53LC production line was located a short distance from our office on the first floor. I visited the line daily to pick up inspection and test results, and to assist with a newly established Quality Index program. Motorola's emphasis on quality goes back a good many years. The "new" subminiature tubes and the unusual speaker design caught my eye too.

Use of Subminiature Tubes

For a 1953 clock radio, a spring-wound clock was a natural choice to use with subminiature tubes. Then, most wrist and pocket watches required winding. In many areas, occasional power interruptions were to be expected, making spring-wound alarm clocks a habitual part of the household. The clock mechanism is probably an adaptation of a pocket watch, or small alarm clock movement. A viable battery-operated clock didn't find its way to Motorola until the transistor-clock-portable Model CX-1 about eight years later.

That year, the use of subminiature tubes was considered to be a harbinger of further miniaturization efforts to come. Transistors were known by name only. Vacuum tubes were all we understood. The subminiature lineup was probably a serious production trial to determine the "real world" benefits, problems, and suitability for wider application of these tubes.

I recall they were not popular with the line workers. They were a little more difficult to handle and install than their 7-pin miniature counterparts and more susceptible to noise, when jarred, and to microphonics. Their service reliability is unknown, but, within a year or so, design emphasis was placed on solid-state circuits. Use of the 7-pin miniature tubes continued until the solid-state circuits were ready.

Other Steps Toward Miniaturization

Another cutting edge feature is visible in the chassis photograph in Jerry Wieland's February article. Notice the presence and particularly the size of the ferrite antenna rod. Ferrite rod antennas were just coming into popular use. Today, rods of that size are usually found only in higher performance sets. Squeezing a conventional flat loop antenna capable of similar performance into the radio's cabinet, along with its large decorative metal grille, clock, and battery pack, would have been quite a problem.

The speaker design was another step toward miniaturization. It was used in other models that year, including the 53H table model and the 63C clock radio, allowing some interesting styling innovations. Motorola undertook the manufacture of the inverted basket speaker at the Quincy plant. The magnetizer, being too heavy for the freight elevator, was set up in the basement of the building, near the Production Engineering Documentation Department. I recall typing the engineer's progress reports and test procedures for the speaker project. By 1956, Motorola had returned to the use of conventional speakers.

Personal Note

As a personal footnote, I left Motorola to attend Central Technical Institute in Kansas City, a 2-year trade school. I returned in a couple of years as a Production Engineering technician and went on tobecome manager of the department in 1968. Through the years, I helped introduce stereo phonographs; transistor portable, auto and home radios; FM automobile radios; FM stereo; automobile reverb units; 8-track stereo; quadraphonic sound; and solid-state TV receivers into production for Motorola, as the plant grew to 900,000 square feet. I left Motorola in 1976, when the Consumer Products Division was sold to Matsushita Electric Co., and the plant was closed.

Photo credits: 1953 Motorola brochure.

(Olin Shuler, 989 Christopher Ct, Quincy, IL, 62381)

�

| [Free Sample] [Books, etc., For Sale] [Subscribe to A.R.C./Renew] [Classified Ads] [Auction Prices] [Event Calendar] [Links] [Home] [Issue Archives] [Book Reviews] [Subscription Information] [A.R.C. FAQ] URL = http://www.antiqueradio.com/Jul04_Shuler_Motorola.html Copyright © 1996-2004 by John V. Terrey - For personal use only. Last revised: June 24, 2004. For Customer Assistance please contact ARC@antiqueradio.com or call (866) 371-0512 Pages designed/maintained by Wayward Fluffy Publications

Antique Radio Classified |