Of Old Radios And Related Items--Published Monthly

Radio and Newspapers in the 1930s

"Just the FAX, Ma'am"BY MICHAEL A. BANKS

Web Edition

In the 1930s attempts were made to commercialize the transmission of text and photographic material by radio facsimile. In this article, Michael Banks covers the Finch facsimile system and the major players in radio facsimile. (Editor)

The Great Depression, with its bank failures, widespread unemployment, and bread lines was a grim period. Business, industry, and the economy shuddered to a halt, along with most people's hopes for the future.

But not everything was stagnant. The march of science and technology continued unabated. Indeed, technology seemed to be the only thing that held any promise for the future. As the decade progressed, electricity was extended into rural areas. Automobiles became faster, safer, and more luxurious. Aviation records were broken as quickly as they were set. Advances in medicine, entertainment, and labor-saving appliances were announced almost daily, and two world's fairs showcased the marvels of technology to come.

Most of these modern marvels were not available to every citizen, but one aspect of technology touched almost everyone -- radio. Even people without electricity or telephone service had radios. Music, news, speeches, and plays had most of North America gathered around their Philco, Emerson, and Crosley sets every evening.

Figure 1. Crosley recommended the use of its Model 1758A high fidelity, 2-band radio to feed its facsimile printer. The radio tuned the BC band and 24 to 47 MHz band. It featured an amplified AVC circuit to control the radio's output level to the printer.As the growth industry of the 1930s, radio was the focus of many experiments and improvements. More powerful transmitters were built, and more reliable receivers poured from the factories. Radio was broadcast from airplanes. Deco style came to both radio and phonograph cabinets. Radios were even showing up in new cars.

Almost anything seemed possible. Anything, that is, but combining radio with newspapers. Radio was the newspaper's worst enemy. It competed for advertising dollars, and lured people away from reading the news. (Why pay a nickel for a paper, when you could listen to the news for free?) The wire services that supplied newspapers with news and photos refused to allow broadcasters access to their services. The one news service that was formed to supply radio stations with news -- the Transradio News Service -- was the object of lawsuits by the conventional news services almost before it started business.

Radio Facsimile Transmission

There were people who hoped to bridge the gap between radio and newspapers, however. One was an engineer named William G.H. Finch. His company, Finch Telecommunications Laboratories, had developed a simple, low-cost system for transmitting and receiving facsimile (now known as FAX) by radio. He applied for his first patent in 1935.

Surprisingly, radio facsimile was nothing new. The first radio facsimile system was patented in 1905, and its earliest application was transmitting weather maps and other data to ships at sea (a practice that continues today). By the early 1920s, news services were transmitting photos by radio facsimile (the first wire photos).

In theory, radio facsimile transmission was nothing more than substituting radio broadcast for telephone wires. But the reality was not that simple. Transmitters and receivers were complicated and temperamental, and usually required highly trained operators. Until Finch's system, radio facsimile equipment was just too complex and costly for most commercial applications.

Finch had three rivals: RCA, General Electric, and Western Electric, each a corporate giant that might have crushed him. But, as a 1937 article in Business Week put it, the Finch system was " the first to come out of the laboratory and into family parlors."

By the end of 1937, Finch had sold three U.S. radio stations on testing his "radio printer" system: WGH in Newport News, Virginia; WHO in Des Moines, Iowa; and KSTP of St. Paul, Minnesota. The broadcasters received FCC permission to transmit radio facsimile signals in September, 1937, and the first transmissions of radio-printed news were made the week of October 15, 1937, in the Minneapolis/St. Paul area. By November, the Iowa and Virginia stations were also broadcasting newspapers.

A Typical FAX Unit

The typical radio facsimile unit resembled a large radio or phonograph cabinet, with the radio receiver and printer housed as one unit within. One example of the receiver/printer equipment was Crosley's high fidelity 2-band radio, Reado printer, and timer, shown in Figures 1, 2 (see print version), and 3.

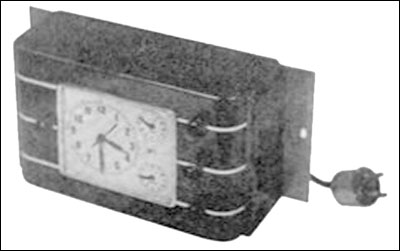

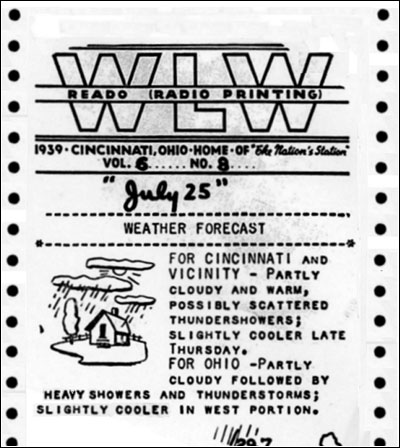

Figure 3. Crosley offered a timer to turn the radio/printer on and off at the appropriate times, thus reducing paper consumption.The system printed the news on a 5-inch wide strip of heat-sensitive paper similar to that used by 1970s printing calculators and FAX machines. The chemical treatment that made the paper heat-sensitive gave the paper a gray or green tint. Text and images were printed in black or dark gray in two columns. Photos and half-tone artwork didn't come through as well as in regular newspapers, but line art reproduced nicely. A typical printout is shown in Figure 4.

Station Participation

Participating broadcasters underwrote the entire effort as an experiment. Each radio station placed 50 receiving sets in its broadcast area at a cost of $125 apiece, an investment of more than $6,000 -- nearly $200,000 today. And that didn't include scanning equipment and transmitter hookups. But broadcasters were optimistic, figuring revenue from advertising and subscriptions would justify the cost.

Figure 4. This printout is an example of information transmitted by radio facsimile.There were a few technical problems, the main one being static. As it turned out, facsimile broadcasts were not as "tolerant" of static as voice broadcasts. A burst of static lasting no more than a fraction of a second could wipe out several pages of a broadcast. However, engineers were confident the problem could be solved.

By March of 1938, the Mutual Network stations (WOR in New York, WLW in Cincinnati, and WGN in Chicago) were conducting experiments with Finch equipment. Before long their owners signed on to the program. WHK in Cleveland, Nashville's WSM, and California radio stations KMJ and KFBK of Fresno and Sacramento, soon followed.

The FCC permitted stations to broadcast printed news between midnight and 6:00 a.m. At the time, radio stations routinely ended their broadcasts and signed off the air at 11:00 p.m. or midnight, so the time slot was ideal for delivering printed news before most people awoke.

Once the receiving sets were in place, the cost to consumers was nominal. Rolls of heat-sensitive paper cost a dollar each, and the estimated cost of the paper used in a week would be ten cents. (Paper consumption was projected to be about five feet per hour of transmission.) The cost of electrical usage in the average home would be increased by only 20 cents per week.

Most stations worked with local newspapers to provide the "radio printed" news. (The exceptions were WHO and WGN, which used Transradio News Service as their news source.) Advertising sales would of course generate profits for all.

RCA and Crosley Join the Crowd

As enthusiasm grew, two radio manufacturers moved in for a share. RCA had experimented with radio facsimile messaging several years earlier, and lost little time getting into the manufacture of radio facsimile receivers. Crosley Radio Corporation, which was heavily committed on the broadcast end through its ownership of WLW, went a step farther. Its owner, Powel Crosley, Jr. licensed the Finch patents and started building a low-cost version of the Finch receiver.

This move by Crosley, whose inexpensive radio sets were in large part responsible for the immense popularity and growth of radio from 1921 on, was a huge vote of confidence for radio printed news. In industry circles, it was taken for granted that, if Powel Crosley, Jr., the man the press had dubbed "the Henry Ford of Radio," was involved in an endeavor, it had to be a sure thing. Even Macy's in New York carried Reado sets. Crosley was always pursuing new commercial applications. Figure 5 (see print version) shows a Crosley advertisement that offers radio facsimile equipment to Amateur radio operators.

A Doomed Service

But, fate conspired against Crosley, Finch, RCA, and all the broadcasters who had invested so much in the radio facsimile system. Money was still tight in the late 1930s, and consumer response was less than overwhelming. This made advertisers leery of the new medium. Without strong advertiser support and subscriptions, the service was doomed. By 1940, radio facsimile newspaper delivery had ended.

The system might have been resurrected after World War II. By then, however, television was making its way into the nation's living rooms. Text and pictures by radio just couldn't compete with television's moving pictures and sound.

William Finch hadn't lost his confidence in FAX as a mass communications medium, however. Right after World War II, he devised a new approach to transmitting newspapers. He intended to FAX them over telephone lines into the homes of millions of paying Americans.

Interestingly, his business plan included local and regional versions of the facsimile newspapers, plus one "super-newspaper" for national consumption. (Shades of USA Today!)

That didn't go over, either. Television and radio were more convenient, and people apparently preferred their newspapers on newsprint. Finch's company went bankrupt in 1952. Fortunately, he was able to license some of this technology to RCA over the next few years.

There's little left of radio facsimile-printed newspapers today, save for the odd receiver/printer in a radio collection or antique shop. That's probably just as well. Even if radio delivery of newspapers hadn't been killed by television, it would never have survived the Internet.

Copyright © 2007, Michael A. Banks

(Michael A. Banks, P.O. Box 175, Oxford, OH 45056.)

A native of the Cincinnati area, Michael A. Banks is co-author of "CROSLEY: Two Brothers and a Business Empire that Transformed the Nation" (Clerisy Press, 2006). He can be reached through http://michaelabanks.com.

| [Free Sample] [Books, etc., For Sale] [Subscribe to A.R.C./Renew] [Classified Ads] [Auction Prices] [Event Calendar] [Links] [Home] [Issue Archives] [Book Reviews] [Subscription Information] [A.R.C. FAQ] URL = http://www.antiqueradio.com/Sep07_Banks_Fax.html Copyright © 1996-2007 by John V. Terrey - For personal use only. Last revised: August 30, 2007. For Customer Assistance please contact ARC@antiqueradio.com or call (866) 371-0512 toll free

Antique Radio Classified |