Of Old Radios And Related Items--Published Monthly

The Saga of Grigsby-Grunow/Majestic Part 1

BY PAUL TURNEY

WEB EDITION

A particular set and an interesting company history can lead to a great deal of research. Paul Turney is able and willing to take on that task, as evidenced by this 2-part article. Part 2 appears later in this issue. (Editor)

My recent acquisition of a Majestic Lido, one of Grigsby-Grunow's modernistic "Smart Sets" from 1933 (see Figure 1) prompted the research that culminated in this article. The company's rapid emergence in the late 1920s as one of the "skyrockets of the boom days," followed by its almost equally speedy demise, dramatically illustrates the perils of unchecked corporate exuberance and risk-taking. Its rise and fall serve as a veritable casebook in the annals of notable and spectacular corporate failures.

The story begins in 1921 with four partners forming the Chicago-based auto parts firm of Grigsby-Grunow-Hinds. By 1925, the company was producing "Majestic" battery eliminators, but this business was soon threatened with obsolescence by the development of AC tubes and socket-powered radios. As a result, in 1928, they turned to manufacturing radios, selling under the Majestic trade name.

Figure 1. Paul Turney's purchase of this Majestic Lido prompted him to write this article.In March of 1928, they raised $1.1 million in a public offering of 29,000 $40 shares. They used the proceeds to finance expansion of the plant on Armitage Ave., to exercise lease options on additional property on Dickens Avenue, parts of which they had already leased that January, and to fund the procurement of radio parts. All this was just in time to catch a rapid updraft in the fortunes of the radio industry. Hinds and the younger brother Grigsby sold out, and the company became Grigsby-Grunow.

The two remaining partners, B.J. Grigsby and W.C. Grunow, became known for belligerent but seemingly brilliant business practices. By the end of May 1929, after just 12 months, profits had soared to around $5,000,000. (Note: There is disagreement on the exact amount among several sources on sales of $49,318,668.) The stock, the "wonder of Wall Street," rocketed to over $1,116 in 1929 for each original $40, following two 4 for 1 splits.

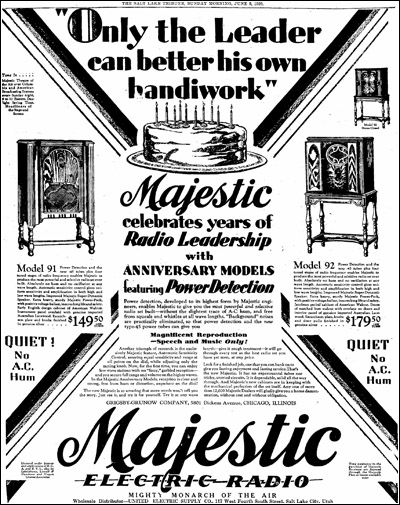

Figure 2. Advertisement (partial) for the Anniversary Models 91 and 92, from the "Salt Tribune," June 9, 1929.In April of 1929, Grigsby-Grunow entered the radio tube business, commencing manufacture under the Majestic name at 5,000 tubes a day. They commented that "an entire year has passed before [we are] ready to say that Majestic Tubes have arrived and are as good as Majestic Radios." That fall, they purchased the La-Salle Corporation, a maker of tubes that had received an RCA license earlier that year.

In an industry first, they opened a "Department of Education" to acquaint educators with all aspects of radio, including, no doubt, the superiority of Majestic radio sets. Some of the brightest minds of the day were recruited to work for Grigsby-Grunow, including for a while Professor Reginald Fessenden, who joined their Special Television Research Department. He was one of the early pioneers of wireless, credited with being the first to have transmitted speech across the Atlantic. By late 1929, 40 engineers were employed in the company's radio labs.

The company continued to expand facilities, announcing in March 1929 a doubling of capacity at 4550 Armitage Ave. and an addition to Dickens Ave. In October, right before the stock market crash, they announced plans for the outright purchase of the 34-acre Dickens Ave. plant, which until that point had been leased from GM. It was to be financed in November with a $40 1 for 7 rights issue to stock holders on record as of November 1.

However, by the time the November 15 issue date arrived, the market had crashed, and the deal was valueless to stockholders, the stock having fallen to around $18. Nevertheless, a New York/Chicago banking syndicate had underwritten the sale at $36 a share, and Grigsby-Grunow received approximately $9,000,000 in proceeds. Upon closing the deal, the syndicate was reported to have "expressed satisfaction with the strong position of the company and confidence that it would retain its position in 1930."

Figure 3. William C. Grunow's English-Tudor style house in Chicago.The "Anniversary Models" 91 and 92

Radio Models 91 and 92, the so-called "Anniversary Models," seen in the advertisement in Figure 2, had been introduced at the Radio Manufacturers Association (RMA) show in June of 1929, along with a combination radio-phonograph. Through the end of the year, Grigsby-Grunow focused on manufacturing just this trio of sets in order to simplify logistics and achieve maximum economies of scale.

Because of their superior loudspeaker technology, like the models they superseded, the three sets sounded better than anything else in the marketplace. They consequently sold like hot cakes; dealers could not keep them in stock, nor get replacements quickly enough to meet demand.

By October, dealers were ordering them by the rail carload to insure adequate supply. In some towns, once the radios rolled in and had been unloaded, convoys of delivery vehicles paraded through the streets, emblazoned with banners proclaiming their arrival.

William C. Grunow, by then extremely wealthy, built the $400,000 palatial English-Tudor style house at 915 Franklin Avenue in Chicago's Forest River shown in Figure 3. It was complete with bowling alley, orange marbled bathrooms, gold faucets and swimming pool. From 1951 to 1963, it was the home of Tony Accardo, a Chicago mobster boss known as the "Big Tuna."

International Outreach and Expansion

When Grigsby-Grunow produced their one millionth radio, it was presented to Henry Ford, that other proponent of mass-production. On August 6, 1929, Herr Max Pruss, navigator onboard the Graf Zeppelin, had just docked at Lakehurst at the start of its round-the-world trip. He had a Model 91 rushed to the hangar so that he could fly it home to Germany on the first leg of the voyage.

He was following the footsteps of Captain Eckener and Chief Engineer Beuerle who had flown Majestics home on earlier transatlantic flights -- Beuerle on the ship's maiden crossing and Eckener on its fourth. Remarking that "they had nothing like it in Germany," they had been singing the high praises of their sets ever since. Pruss later went on to fame as the captain of the ill-fated Hindenburg.

Other reports from late October 1929 detail how, in a blaze of publicity, W.C. Grunow presented each of the 40 members of the Graf Zeppelin's crew with a Majestic radio. Presumably this took place upon conclusion of the round-the-world trip, prior to the ship's departing Lakehurst for Friedrichshafen. The sets were shipped to Germany by boat on account of their "great weight," free of charge by the Hamburg-American line.

Germans would soon, however, be able to buy Majestic radios in Germany, for Grigsby-Grunow had announced in June their intention to organize a company in England that would manufacture Majestics for distribution in Europe, Asia and Africa. Plans were also afoot for a plant in Canada.

By November of 1929, sources claimed that from 11,000 to as many as 15,000 people were employed at the company's eight giant plants, turning out some 5,000 to 6,000 radios and 30,000 to 60,000 tubes daily. Their payroll was the second biggest in all of Chicago, and the cabinet plant was the largest furniture factory in the world, with five lumber mills devoted to supplying it.

Reports in September described how 150 tons of steel, 16,000 pounds of tinfoil, 12,000 pounds of paper, enough speaker wire to encircle the globe, 5,000 pounds of aluminum and 20 tons of wax, along with hundreds of thousands of smaller items, made their way to the factory daily in 37 railcars. Each day 40 cars filled with finished goods left the plant. Plans were afoot for expansion to 7,000 sets a day by December, and tube production was set to increase from 30,000 to 100,000 daily within three months.

Grigsby-Grunow planned a sizable advertising budget for the upcoming year. Their slogan was "Mighty Monarch of the Air." All this for a company that just five years earlier had employed only 40 people and had made its first radio set only a year and a half ago.

Early Effects of the Depression

In the aftermath of the October 1929 stock market crash, as the Great Depression began to bite, things were at first slow to change at Grigsby-Grunow. In March of 1930, in an early sign of trouble, the company announced it would not pay a 50 cent dividend. November and December 1929 holiday sales had fallen to just 9 percent of total compared with 34 percent in 1928. In spite of price reduction in early November in a preemptive bid to maintain sales, much of the plant had ended up idle during the holiday period. Malicious rumors were circulating as early as December 1929 planting the idea of Grigsby-Grunow's impending bankruptcy. The company and its dealers protested that such claims were, in fact, "ridiculous," and that "the fact of the matter is that Majestic is one of the most financially sound industrial plants in the country."

Figure 4. A Majestic Model 59, one of the "Smart Sets."Sales did recover during January and February of 1930, however, ending the year through Feb 28 at $54,149,153 compared to $37,587,328 for the previous year. For the quarter ending March of 1930, they sold 221,179 radio sets versus 244,237 a year earlier. By the end of May 1930, yearly sales peaked at the all-time record of $61,330,217, but profits were lower, at $1,745,648 versus around $5,000,000 the year before.

The stock price, which had been close to its all-time high of $70 in early October 1929 shortly before the crash, closed out May 1930 at around $27, having dipped as low as $14 in January. Nevertheless, because of the 16-way split, these prices were still fabulously ahead of the stock's initial $40 offer price.

A Diversifying Venture

In the summer of 1929, the partners announced they would build electric refrigerators, having perfected, they claimed, a design that would give GM's Frigidaire line "a real race." In due course, in April 1930, they announced the formation of a new affiliate, "Majestic Household Utilities," to handle this business.

Grigsby-Grunow held almost 25 percent of the new company's stock, giving them effective control of the enterprise, and the balance, in an unprecedented move, was offered on the Chicago stock exchange even before the new company had opened its doors. In a throwback to the good old days, speculators soon kicked up the share price from its subscription value of $25 to a high of $74. Grigsy-Grunow hoped the new venture would even out their business, as refrigeration sales tended to peak during the summer and radio sales in the winter. Their slogan was "Mighty Monarch of the Arctic."

However, there were repeated delays in starting up production, which would not get underway until October 1930. Moreover, the company had been structured with high fixed costs, and it soon had solvency problems. On March 10, 1931, motions were passed for Majestic Utilities' consolidation with affiliate Grigsby-Grunow, and for a $5,000,000 bond sale to raise capital. The merger took place the next day.

Competition was intense in the risky radio business as sets became smaller and less profitable. Grigsby-Grunow's sales could not sustain the enormous infrastructure that had been put in place during the rapid expansion, and the empire started a precipitous decline as losses mounted. Through May of 1929, the value of plant and property held by the company was listed at $3,611,088, but a year later this had increased to $9,233,415, mainly because of the acquisition of Dickens Avenue.

For early February 1931, set production was reported at 2,000 daily with the plants running five days a week and employing between 2,000 and 4,000 workers. For the year ending May 31, 1931, three months after the merger with Majestic Utilities, a net loss of $2,169,761 was recorded versus $1,745,648 net profit a year earlier. Profit at Majestic Utilities since the merger on March 11 was $112,374. The stock slumped to new lows of around $3 a share. The situation worsened and in 1932 the stock traded for a while at a low of 40 cents a share.

Magnavox Litigation

When it rains it pours, and Grigsby's problems were compounded by litigation and royalty issues. Much of their early success was attributable to the electrodynamic speakers they manufactured and used in their radios under an RCA license.

It had been the idea of William Lear, later of Avionics fame, but then a Grigsby-Grunow employee, to adopt the dynamic speaker for use in radio sets. As a result, the first Majestic radios sounded superior to anything else on the market. However, in early 1930, Magnavox filed suit alleging infringement of their Jensen and Pridham dynamic speaker patents, even claiming exclusive rights to use of the word "dynamic."

Rumors started of a merger of the two companies that would take place in the event of crippling damages being awarded against Grigsby-Grunow. Struggling Magnavox, based in the West and looking for plants in the East (possibly Chicago) to reduce their cross-continental freight costs, restructured their company, some sources claiming in anticipation of the merger.

A settlement was reached in the spring of 1931, without merger, whereby Grigsby-Grunow would pay Magnavox a $100,000 cash down-payment plus a 10 cent royalty on each Majestic radio sold, a number some estimated at 4,000,000 sets, for a total of $400,000 in royalties. Magnavox was soon supplying Grigsby-Grunow with all their loudspeakers. At the time, Magnavox had ongoing litigation with almost every radio manufacturer in the U. S., as most had caught on and were using dynamic speakers, a fact which lessened Grigsby-Grunow's stand-out advantage and further hastened the erosion of their fortunes.

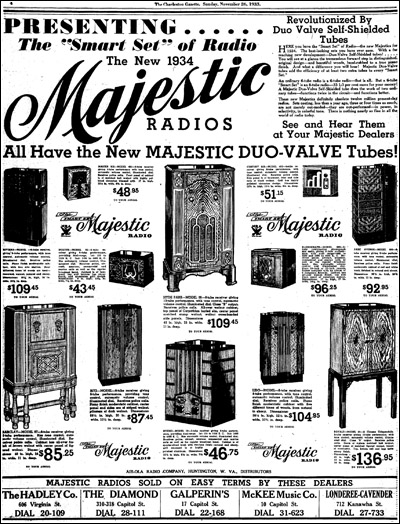

Figure 5. An advertisement (partial) for Majestic's 1934 "Smart Sets" line.RCA Royalty Issue

The Magnavox dispute was only one of Grigsby-Grunow's ongoing litigation woes. The RCA "radio trust" was collecting royalties of 7.5 percent from them, at one point on everything they shipped, including cabinets and even packing crates. Through June of 1930, they had paid RCA a cool $6,000,000 (about $73,000,000 in 2009 dollars).

Grigsby-Grunow requested that the Radio Manufacturers Association (RMA) support a monopolies investigation of RCA by the federal government, following the filing of a federal suit against the "trust" that May. The RMA refused, and in June, Grigsby-Grunow resigned its membership, though the RMA insisted they were asked to do so.

On June 26, Grigsby-Grunow filed a $30,000,000 suit against the "radio trust" claiming triple damages from alleged restriction of trade through the operation of an illegal pool of 4,000 patents. The RCA "radio trust" was dissolved in November of 1932, and the $30,000,000 Grigsby-Grunow filing was dismissed on Jan 17, 1933, following "amicable concessions." Grigsby-Grunow, nevertheless, expressed satisfaction at the outcome.

Much of the blame for the company's ills was attributed to the "shouting, swearing" William Grunow, known for his bulldog style and foul mouth. When the company went to the banks in late 1930 for aid, they insisted that Grunow go as a precondition to providing the aid. On January 23, 1931, the scapegoat Grunow was voted out and poker-faced Grigsby in as president. The plan was to change the name of the company to the Majestic Corporation, though as we know, this never occurred.

Ousted Grunow went on to form General Household Utilities, which manufactured Grunow radios. When that later failed, he ended up successfully running the Val-Lo-Will Chicken Farm.

The Smart Sets

Grigsby-Grunow's standard fare in radio sets had been mostly massively constructed models in large classically styled cabinets for which a premium could be charged, but the public's tastes during the Depression were changing, and sales had fallen. In 1933, in an effort to revive their fortunes, the company introduced their 1934 line of "smart sets," beginning predominantly in the early summer with table models. Figure 4 shows a Majestic table Model 59 from my collection. They rounded it out with four consoles, the Lido, Ritz, Park Avenue and Riviera, along with several more traditional consoles, in late September. Figure 5 shows an advertisement for the "Smart Set" line.

The new line was inspired by the modernistic architecture of the Chicago "Century of Progress" exposition, and based upon design patent #90,680 for one of the sets, the Model 411. Much of the styling was probably the work of Chicago designers/engravers Rosenow & Co. This same company would reportedly later go on to style Zenith's small, white-dial, chrome-front models, introduced in mid-1934. Certainly the similarity in styling between some of the Zenith and Majestic models (e.g. Majestic 161 and Zenith 829) is striking.

By and large, the new line, comprising mainly smaller, less profitable sets, represented a radical departure from the company's earlier offerings. The models were extensively advertised, and the attractive, stylish designs were an instant hit, with the result that domestic and export sales rose significantly during the six months through November 1933.

In October alone, with the company employing 5,000 workers, shipments were reported to have totaled 66,543 radios, with the backlog exceeding 39,000 units by month's end. In July, normally a slow month, shipments were 26,000 sets compared with a mere 275 sets the previous July. Overall, by the fall, unit sales were up more than eight-fold over a year earlier.

Newspapers reported on "Majestic's return" and of their "record boom" and of the "great demand for their new sets." Shipments were claimed to be at levels the likes of which the company had not experienced since the heady days of 1929, when they were Number 1 in the industry. It seemed like the good old days had returned. Executives of the company credited the National Recovery Act (NRA) of June 1933 as also helping to boost their sales. In addition, various RMA initiatives during the fall of 1933 to promote radio sales were likely to have helped.

Part 2 of this article, with references for both parts, appears later in this issue.

Paul Turney has been collecting vintage radios on and off since 2001, focusing on sets from the 1930s and 1940s. You can see more of his collection at his website www.tuberadioland.com.

|

[Free Sample] [Books, etc., For Sale] [Subscribe to A.R.C./Renew] [Classified Ads] [Auction Prices] [Event Calendar] [Links] [Home] [Issue Archives] [Book Reviews] [Subscription Information] [A.R.C. FAQ]URL = http://www.antiqueradio.com/SepOct10_Turney_Grigsby-Grunow_Part1.html Copyright © 1996-2010 by John V. Terrey - For personal use only. Last revised: September 13, 2010. For Customer Assistance please contact ARC@antiqueradio.com or call (866) 371-0512 toll free Antique Radio Classified |